The Power and Requirements of an Effective Control System

In management, a control system is far more than a tool for catching errors; it’s a dynamic, forward-looking framework that grants an organization the power to turn its strategic plans into reality. An effective control system provides the crucial feedback loop that enables alignment, drives improvement, and fosters adaptability. However, this power is only unlocked when the system itself is designed with a clear set of principles, or requirements, in mind.

The Strategic Power of Effective Control

A well-designed control system gives an organization four strategic “superpowers” that are essential for thriving in the competitive US market of 2025.

The Power to Align Strategy with Action

An effective control system ensures that the day-to-day work of every employee directly contributes to the high-level strategic goals of the company. It bridges the gap between the boardroom and the front line.

The Power to Drive Continuous Improvement

By providing objective, timely feedback on performance, control systems highlight inefficiencies and weaknesses. This data empowers teams to learn, innovate, and constantly refine processes, fostering a culture of continuous improvement.

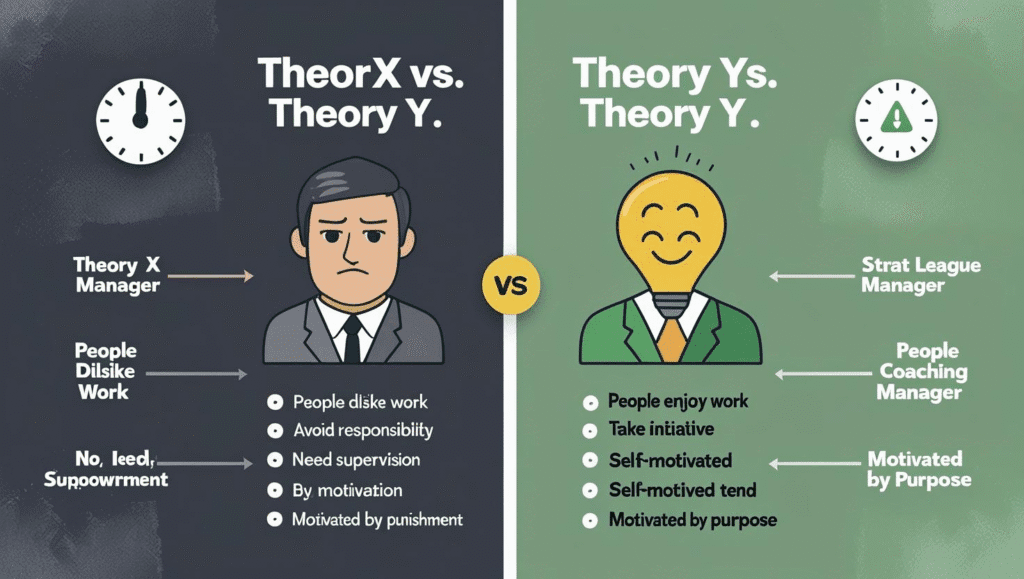

The Power to Empower Employees

Good control is not about micromanagement. It’s about providing clear goals and a transparent “scoreboard.” This empowers individuals and teams to manage their own performance, make informed decisions, and take ownership of their results.

The Power to Anticipate and Adapt

Control systems act as an early-warning mechanism. By flagging deviations from the plan, they can signal a larger market shift, a new competitor action, or an internal problem, allowing management to adapt proactively rather than reactively when it’s too late.

The 7 Requirements for an Effective Control System

To unlock the strategic power described above, a control system must be designed with the following essential characteristics in mind. A system that fails to meet these requirements will likely be ineffective, ignored, or even counterproductive.

-

1. Accurate and Objective

The information and data the control system provides must be accurate and based on objective facts. If the data is flawed or biased, the decisions based on that data will also be flawed. The system must be a trusted source of truth.

Example: A sales manager’s control system should be based on verified sales figures from the accounting department, not on subjective estimates from the sales reps.

-

2. Timely

Information must be delivered to managers quickly enough for them to take meaningful corrective action. A report on a massive budget overrun that arrives three months after the fact is a historical document, not a control tool.

Example: A fast-food restaurant manager needs a daily report on food costs, not a monthly one, to quickly address issues like waste or theft.

-

3. Flexible

The business environment is not static, and neither are plans. An effective control system must be flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances. It should be able to accommodate new goals, unforeseen events, or updated plans without having to be completely redesigned.

Example: When a hospital faces a sudden patient surge, its staffing and budget control systems must be flexible enough to allow for authorized overtime and emergency supply purchases.

-

4. Clear and Simple

A control system is useless if the people who need to use it don’t understand it. Reports and dashboards should be clear, concise, and free of jargon. The system should present information in a simple, understandable format that highlights key deviations and makes it easy to see what’s important.

Example: A manufacturing plant’s quality control dashboard should use a simple red-yellow-green light system to indicate production line status, rather than a complex spreadsheet with dozens of variables.

-

5. Cost-Effective

The benefits derived from a control system must be greater than the cost of implementing and operating it. A complex, expensive system to track minor office supply usage, for example, would not be cost-effective. The resources spent on control should be proportional to the importance of the activity being controlled.

Example: A small retail business might use a simple, free spreadsheet to track daily sales (cost-effective), while a large corporation like Amazon would invest millions in a sophisticated real-time inventory control system because the benefit of avoiding stockouts is immense.

-

6. Focused on Strategic Points

It is inefficient and often impossible to control every single aspect of an organization’s performance. Effective systems focus on “critical control points”—the key areas where monitoring is essential for the success of the overall plan. These are the areas where failure would have the greatest impact.

Example: An airline focuses its most rigorous control efforts on aircraft maintenance, on-time departures, and fuel consumption, because these are strategically critical to its safety and profitability. They spend less time controlling the brand of coffee served in the lounge.

-

7. Motivational and Accepted

The control system should be designed in a way that employees perceive it as fair, helpful, and necessary. If it is seen as a punitive tool for placing blame, employees may resist it or try to “game the system.” When controls are linked to clear goals and provide objective feedback, they can be highly motivational.

Example: A software development team uses a project management tool that tracks progress against deadlines. When the team sees themselves hitting milestones, it’s motivating. If the tool were instead used by the manager to criticize them for every minor delay, it would become demotivating.

Conclusion: The Compass, Not the Cage

The power of a control system is unlocked only when it is designed with these key requirements in mind. An effective system is not a rigid cage that restricts employees; it is a compass that provides direction and feedback, enabling the entire organization to navigate challenges and confidently reach its strategic destinations. By focusing on accuracy, timeliness, clarity, and motivation, managers can build control systems that empower their teams and drive sustainable success.

Frequently Asked Questions

Strategic control is a long-term, high-level process managed by top executives to ensure the company is meeting its overall strategic goals. It answers the question, “Are we doing the right things?” Operational control is a short-term, day-to-day process managed by front-line and mid-level managers to ensure specific tasks are being performed correctly and efficiently. It answers the question, “Are we doing things right?”

Technology has revolutionized control. Real-time dashboards (like Salesforce for sales teams), inventory management software, and project management tools (like Asana or Jira) have made control systems much more timely and accurate. They allow managers to see performance data instantly, rather than waiting for manual reports, enabling much faster corrective action.

Imagine a small office of 10 people installing a sophisticated, time-tracking security system that requires every employee to log every single minute of their day in different categories, and it takes 15 minutes per day for each person to fill out. The cost in lost productivity (2.5 hours per day across the team) and the system’s price would far outweigh the benefit of knowing exactly how much time was spent on minor administrative tasks.