The Essential Relationship Between Stakeholders and Corporate Governance

In the complex ecosystem of modern business, a company’s success is determined by more than just its balance sheet. Long-term value, resilience, and reputation are built on a foundation of trust and accountability. This foundation is constructed and maintained through corporate governance, and its strength is tested by the company’s relationship with its stakeholders. Understanding this dynamic interplay isn’t just academic—it’s essential for anyone looking to build or evaluate a sustainable 21st-century business.

This article explores the critical link between those who have a stake in a company’s success and the systems designed to direct and control it. We will delve into the competing theories of governance, identify key stakeholder interests, and examine how a modern, inclusive approach to governance creates lasting value for everyone involved.

Defining the Core Concepts

Corporate Governance: This is the system of rules, practices, and processes by which a company is directed and controlled. It encompasses the roles and responsibilities of the board of directors, management, shareholders, and other stakeholders, defining the framework for setting and achieving company objectives.

Stakeholders: A stakeholder is any individual, group, or organization that can affect or is affected by a company’s actions, objectives, and policies. This broad category includes not only investors but also employees, customers, suppliers, governments, and the surrounding community.

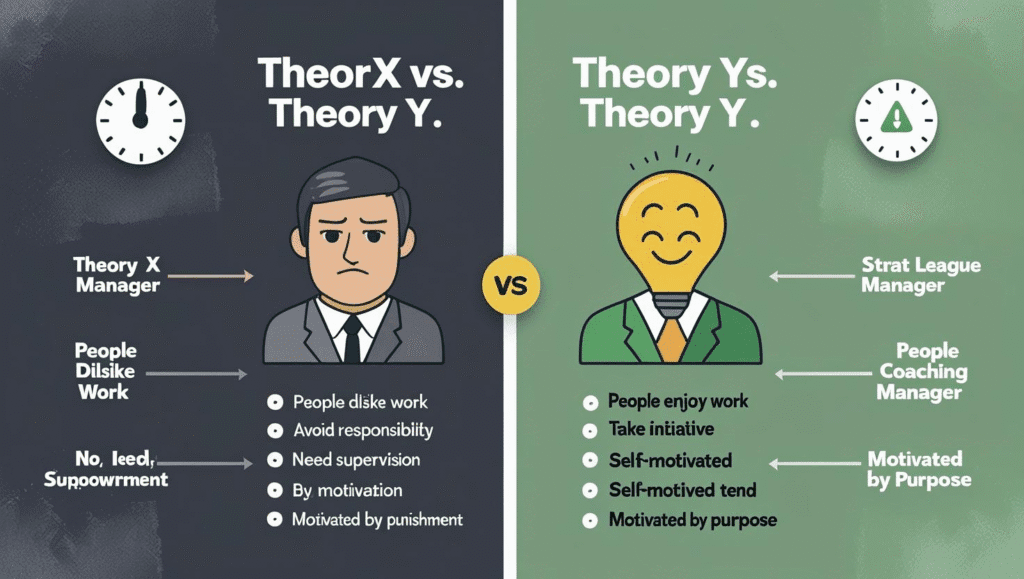

Two Views of Governance: Shareholder Primacy vs. Stakeholder Theory

The relationship between governance and stakeholders is defined by a central question: To whom is the board of directors ultimately accountable? The answer to this has traditionally fallen into two camps.

The Traditional View: Shareholder Primacy

Championed by economist Milton Friedman in the 1970s, this model asserts that a company’s sole social responsibility is to increase its profits for its shareholders. In this view, the board has one primary fiduciary duty: maximize shareholder wealth. Other stakeholders are only considered instrumentally, meaning they are managed to the extent that it helps achieve the primary goal of shareholder return.

The Modern View: Stakeholder Theory

Stakeholder Theory, developed by R. Edward Freeman and others, presents a more inclusive model. It argues that a business operates within a complex web of relationships and that its long-term success depends on creating value for *all* of its stakeholders, not just those who own its stock. The role of the board, therefore, is to act as a trustee for all stakeholders, balancing their often-competing interests to ensure the company’s long-term health and sustainability.

| Aspect | Shareholder Primacy Model | Stakeholder Theory Model |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Duty of the Board | Maximize shareholder wealth (stock price, dividends). | Balance the interests of all stakeholders to ensure long-term value. |

| Time Horizon | Often encourages a short-term focus (quarterly earnings). | Encourages a long-term focus on sustainability and resilience. |

| Measure of Success | Primarily financial metrics (profit, share price). | A “balanced scorecard” including financial, social, and environmental performance (ESG). |

| View of Other Stakeholders | Instrumental; a means to the end of shareholder profit. | Intrinsic; their interests have value in and of themselves. |

| Associated Risks | Can lead to ignoring negative externalities (e.g., pollution) and fosters short-term thinking. | Can be complex to manage competing interests and measure performance. |

Identifying Key Stakeholders and Their Governance Interests

Effective corporate governance must understand and address the specific expectations of its various stakeholder groups. A failure to manage these relationships can lead to significant operational, financial, and reputational risk.

- Shareholders/Investors: They provide capital and expect a return. Their governance interests include transparency in financial reporting, a clear strategy for profitability, and accountability from the board for stock performance.

- Employees: They provide the labor and expertise that create value. Their interests include fair compensation and benefits, safe working conditions, opportunities for development, job security, and an ethical corporate culture.

- Customers: They are the source of revenue. They expect high-quality products/services at a fair price, excellent customer service, and assurance that their data is protected. Product safety and ethical marketing fall under this purview.

- Suppliers and Partners: They are critical to the supply chain. They expect fair and transparent contract terms, prompt payment, and a stable, long-term business relationship.

- Community: This includes local residents and society at large. Their interests involve the company acting as a good corporate citizen—minimizing environmental impact, creating jobs, paying its fair share of taxes, and contributing positively to community life.

- Regulators and Government: They set the legal framework. They expect full compliance with all laws and regulations, from labor standards and environmental protection to financial reporting and anti-corruption laws.

How Governance Mechanisms Serve Stakeholders

The structures of corporate governance are the tools a company uses to manage its relationship with stakeholders.

- The Board of Directors: A well-composed board with diverse skills and backgrounds is better equipped to understand and represent a wide range of stakeholder interests. Independent directors, in particular, can provide objective oversight to prevent management from prioritizing one group (e.g., their own compensation) over others.

- Executive Compensation: Governance dictates how executives are paid. Tying bonuses not just to share price but also to metrics like employee satisfaction, customer retention, and environmental targets can align leadership’s goals with those of a broader set of stakeholders.

- Transparency and Reporting: Modern governance demands more than just a financial report. Integrated reporting, which includes details on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance, provides all stakeholders with a more complete picture of the company’s value creation and risk management processes.

- Code of Conduct and Ethics: This is a cornerstone of governance that explicitly sets the rules for how the company and its employees will interact with all stakeholders, ensuring fairness, integrity, and respect.

Conclusion: A Symbiotic Relationship for a Sustainable Future

The relationship between stakeholders and corporate governance is not a one-way street; it is a symbiotic partnership. Strong governance provides the structure for listening to, engaging with, and balancing the needs of all stakeholders. In turn, engaged stakeholders provide the company with vital resources—capital, labor, revenue, and a social license to operate.

While the shareholder-centric view once dominated, the global consensus is shifting. Today’s most resilient and successful companies recognize that creating long-term value for shareholders is the *result* of creating value for all stakeholders. Effective, inclusive, and transparent governance is the essential mechanism that makes this possible.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the main difference between a stakeholder and a shareholder?

A shareholder is a specific type of stakeholder who owns at least one share of a company’s stock, making them a part-owner. A stakeholder is a much broader term that includes anyone with an interest in the company’s operations and success. This includes employees, customers, suppliers, the community, and the government, in addition to shareholders. All shareholders are stakeholders, but not all stakeholders are shareholders.

Is stakeholder theory the same as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)?

They are closely related but distinct concepts. Stakeholder theory is a model of corporate governance that dictates who the board should be accountable to—arguing for a wide range of stakeholders. CSR refers to the specific actions, policies, and initiatives a company undertakes to be socially accountable. In essence, stakeholder theory provides the ‘why’ and the ‘who’ for governance, while CSR provides the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ for the company’s social and environmental actions.

Who is the most important stakeholder?

This is a central debate in corporate governance. The traditional Shareholder Primacy view argues that shareholders are the most important, as the company’s primary duty is to maximize their wealth. The modern Stakeholder Theory argues that no single group is inherently more important. Instead, the board’s role is to strategically balance the often-competing interests of all stakeholders to ensure the long-term health and sustainability of the entire enterprise.

How does a company’s board balance conflicting stakeholder interests?

Balancing conflicting interests is one of the most difficult challenges for a board of directors. They do this through strategic decision-making, prioritization, and clear communication. For example, a decision to invest in costly new safety equipment may reduce short-term profit (a concern for some shareholders) but increases employee safety (a key interest of employees) and reduces long-term legal risk (a benefit to all). Effective governance involves making these trade-offs transparently and justifying them based on the company’s long-term strategic goals and ethical values.